The Emirate of Ras al Khaimah has provided one of the fuller archaeological record of the Southeast Arabian Peninsula. Indeed, all major cultural horizons since the Ubaid period (5000-3200 BC) have been reported on its territory (de Cardi et al., 1994 ; Vogt et al., 1987 ; Kennet, 2012). This continuity through time is certainly linked, at least partially, to the natural hospitality of the area. Ras Al Khaimah is at the interface between the Rub al Khali dunes, the Persian Gulf shores and the calcareous northern part of the Hajar Mountains. The plurality of micro-environments created by the encounter of these three domains offers a privileged terrain for human occupation (Kennet, 2012). The vicinity of the coast and there lagoons provided fish, permitted pearl production and enabled inter-regional trades. The large aquifer, fed by the many wadis which cut into the mounts, provided fertile alluvial soils and allowed for the cultivation of date palms as well as vegetables and cereals. The most part of Ras Al Khaimah territory is then particularly suitable for oases implantation. However, the story of these entities remains poorly known, the numerous remains excavated are rarely directly connected to agricultural activities. Nonetheless, the agrarian value of this territory has been known for a long time by the archaeologists (Kennet, 2002 ; Velde, 2012).

Our objective for the present project is to adopt innovative paleoenvironmental approaches to study the three main oases of this Emirate and refine the evolution of agrarian landscapes (Figure 1). This work will be a major contribution to our historical knowledges of Ras al Khaimah as it will allow a better understanding of the role of environment, agrarian practices and hydraulic techniques in the evolution of these settlements.

The opening of test pits and geophysics surveys will be conducted in each oases, in order to study the existence and preservation of ancient agricultural deposits. Their respective watersheds will be surveyed to understand how they feed the palm groves with water and soils. All the identified features, natural or anthropic will be mapped and analysed in a GIS. Ethnoarchaeological interviews will be conducted with local population to comprehend traditional agrarian practices. Finally, a large range of geoarchaeological and paleoenvironmental analyses will be performed: pedo-sedimentary, micromorphological and geochemical analyses, shells and phytoliths studies, radiocarbon and OSL datings.

Figure 1: Localisation of the 3 studied oases in Ras al Khaimah

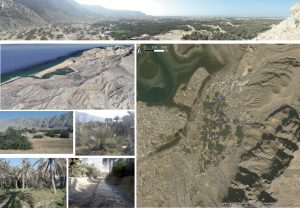

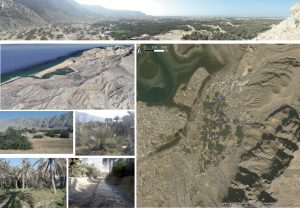

The first space studied in 2017 will be the oasis of Dhayah, located in a small enclave confined by a mangrove and calcareous mountains (Figure 2). Wadi Suq burials and the Iron Age fortress testify for a possible 4000 years occupation and offer a good archaeological potential to this area.

Figure 2: Photographs and satellite view of the Dhayah oasis

The Shimal oasis will be explored in 2017 and 2018 (Figure 3). This area has provided continuous archaeological remains, from the Umm an-Nar period (2700-2000 BC) to the most recent periods (Kennet, 1997) and is located in the Sir plain, which constitutes with the Jiri plain “the agricultural core of northern Ra’s al-Khaimah” (Kennet, 2002). Moreover, the palm-grove of Shimal has been linked with the gardens and the cultivated areas of the medieval town of Julfar, important trading harbour (Velde, 2012). Then, this area seems to have an excellent potential to help us reconstructing the history of the oases, most likely strengthened by the constant outwash from the Wadi Bih which allows for a good preservation of past soils.

Figure 3: Satellite view of the Shimal oasis

The oasis of Khatt will be investigated in 2019 (Figure 4). Evidence for its occupation range from the earliest periods (Lithic period) up to present day (de Cardi et al., 1994). We have to mention the presence of Nud Ziba, a large unexcavated tell which preserves a large period of time, at least since the Late Bronze Age (Kennet and Velde, 1995).

Figure 4: Photographs and satellite view of the Khatt oasis

Bibliography

- B. de Cardi, D. Kennet and R. L. Stocks (1994): Five thousand years of settlement at Khatt, UAE, in: Proceedings of the Seminar for Arabian Studies, Vol. 24, Proceedings of the Twenty Seventh Seminar For Arabian Studies (22-24 July 1993), London, pp. 35-95

- D. Kennet (2012): Archaeological History of the Northern Emirates in the Islamic Period: An Outline, in: Fifty years of Emirates Archaeology – Proceedings of the Second International Conference on the Archaeology of the United Arab Emirates (D. Potts and P. Hellyer, eds.), Abu Dhabi Authority for Culture and Heritage, Abu Dhabi, pp. 189-201

- D. Kennet (2002): The development of northern Raʾs al-Khaimah and the 14th-century Hormuzi economic boom in the lower Gulf, in: Proceedings of the Seminar for Arabian Studies, Vol. 32, Papers from the thirty-fifth meeting of the Seminar for Arabian Studies (19-21 July 2001), Edinburgh, pp. 151-164

- C. Velde (2012): The geographical history of Julfar, in: Fifty years of Emirates Archaeology – Proceedings of the Second International Conference on the Archaeology of the United Arab Emirates (D. Potts and P. Hellyer, eds.), Abu Dhabi Authority for Culture and Heritage, Abu Dhabi, pp. 214-221

- B. Vogt, J. Häser and C. Velde (1978): Archäologische Forschungen in Shimal, Ras al-Khaimah (Vereinigte Arabische Emirate)’, in: Archiv fur Orientforschung XXXIV, Vienna, pp. 237-242

Field team

- Louise Purdue (director), geoarchaeology

- Julien Charbonnier (co-director), archaeology & ethnoarchaeology

- Sophie Costa, geoarchaeology

- Aline Garnier, phytolithology

- Hatem Djerbi, malacology

- Maël Crépy, geomorphology

- Gourguen Davtian, geomatics

- Clément Virmoux, geophysics

Lab team

- Ian Bailiff, OSL dating

- Lisa Snape-Kennedy, OSL dating

- Frank Preusser, OSL dating

- Thierry Blasco, chemistry

- Arnaud Mazuy, chemistry

- Linda Herveux, palaeobotany

- Alain Carré, palaeobotany

Traduction française : Oasis Ras al Khaimah

L’Emirat de Ras el Khaimah a livré l’un des enregistrements archéologiques les plus complets du Sud-Est de la péninsule arabique. En effet, l’ensemble des principaux horizons culturels depuis le Néolithique a été mis au jour sur son territoire (de Cardi et al., 1994 ; Kennet, 2012, Vogt et al., 1978). Cette continuité temporelle est certainement à mettre en lien, au moins partiellement, avec l’hospitalité naturelle de la région. Ras el Khaimah est effectivement situé à l’interface des dunes du Rub al Khali, des côtes du Golfe Persique et des montagnes calcaires de la partie nord de la chaine des Hajar. La pluralité des micro-environnements créés par la rencontre de ces trois domaines semble offrir un terrain privilégié pour l’occupation humaine (Kennet, 2012). La proximité de la côte et de ses lagons permet pêche et production perlière et favorise les échanges inter-régionaux. Le large aquifère, alimenté par les nombreux wadis qui incisent les reliefs calcaires, fournit des sols alluviaux fertiles, appropriés à la culture des palmiers dattiers comme à celle des légumes et céréales. La grande majorité du territoire de Ras el Khaimah est donc particulièrement adaptée à l’implantation d’oasis. Toutefois, l’histoire de ces entités reste peu connue, les nombreux vestiges mis au jour étant rarement connectés aux activités agricoles. Pourtant, la valeur agraire de ce territoire est connue depuis longtemps des archéologues (Kennet, 2002 ; Velde, 2012).

Notre objectif pour ce projet est donc d’adopter une approche paléoenvironnementale innovante afin étudier les trois principales oasis de cet Emirat et de préciser l’évolution de ces paysages agraires (Figure 1). Ce travail constituera une contribution majeure à l’histoire de Ras el Khaimah mais permettra également une meilleure compréhension du rôle de l’environnement, des pratiques agraires et des techniques hydrauliques dans l’évolution de ces occupations.

Des sondages géoarchéologiques et géophysiques seront réalisés dans chacune des oasis afin d’apprécier l’existence et la préservation d’anciens niveaux cultivés. Les bassins versants respectifs seront prospectés pour comprendre le fonctionnement des paysages qui les alimentent en eau et en sol. Tous les éléments constitutifs des paysages actuels ou anciens repérés, qu’ils soient naturels ou anthropiques, seront cartographiés et spatialisés sous SIG. Des enquêtes ethnoarchéologiques seront menées auprès de la population locale afin de référencer les pratiques agraires traditionnelles. Enfin, un large ensemble d’analyses géoarchéologiques et paléoenvironnementales sera réalisé sur les paléosols ainsi mis au jour : analyses pédo-sédimentaires, micromorphologiques et géochimiques, études de la malacofaune et des phytolithes, datations radiocarbone et OSL.

L’oasis de Dhayah sera la première à être investiguée en 2017. Située dans une petite enclave confinée par des mangroves et par les montagnes calcaires (Figure 2), les tombes Wadi Suq qui y ont été mises au jour, ainsi que la forteresse datant de l’Age du Fer témoignent d’une possible occupation depuis le deuxième millénaire avant notre ère.

L’oasis de Shimal sera explorée en 2017 et 2018 (Figure 3). Cette zone a déjà prodigué un enregistrement archéologique continu depuis la période Umm an-Nar (2700-2000 BC) jusqu’aux périodes les plus récentes (Kennet, 1997) et est située dans la plaine de Sir, qui constitue, avec la plaine de Jiri, « le noyau agricole du Nord de Ras el Khaimah » (Kennet, 2002). La palmeraie de Shimal a été mise en relation avec les terres exploitées de la ville de Julfar, important port de commerce médiéval (Velde, 2012). Ce territoire présente donc un excellent potentiel pour la compréhension de l’histoire des oasis. Ce potentiel se voit renforcé par l’épandage constant de sédiments issus du Wadi Bih, qui permet une meilleure préservation des sols anciens.

L’oasis de Khatt sera sondée en 2019 (Figure 4). Les preuves de son occupation remontent des périodes les plus anciennes (Lithics periods) jusqu’aux périodes récentes (de Cardi et al., 1994). Nous devons mentionner la présence du site de Nud Ziba, large tumulus qui n’a pas encore pu être fouillé, et qui enregistre, d’après les seules coupes étudiées, une longue période de temps, au moins depuis la fin de l’Age du Bronze (Kennet et Velde, 1995).

Bibliographie

B. de Cardi, D. Kennet et R. L. Stocks (1994) : Five thousand years of settlement at Khatt, UAE, in: Proceedings of the Seminar for Arabian Studies, Vol. 24, Proceedings of the Twenty Seventh Seminar For Arabian Studies (22-24 July 1993), London, pp. 35-95

D. Kennet (2012) : Archaeological History of the Northern Emirates in the Islamic Period: An Outline, in: Fifty years of Emirates Archaeology – Proceedings of the Second International Conference on the Archaeology of the United Arab Emirates (D. Potts and P. Hellyer, eds.), Abu Dhabi Authority for Culture and Heritage, Abu Dhabi, pp. 189-201

D. Kennet (2002) : The development of northern Raʾs al-Khaimah and the 14th-century Hormuzi economic boom in the lower Gulf, in: Proceedings of the Seminar for Arabian Studies, Vol. 32, Papers from the thirty-fifth meeting of the Seminar for Arabian Studies (19-21 July 2001), Edinburgh, pp. 151-164

C. Velde (2012) : The geographical history of Julfar, in: Fifty years of Emirates Archaeology – Proceedings of the Second International Conference on the Archaeology of the United Arab Emirates (D. Potts and P. Hellyer, eds.), Abu Dhabi Authority for Culture and Heritage, Abu Dhabi, pp. 214-221

B. Vogt, J. Häser et C. Velde (1978) : Archäologische Forschungen in Shimal, Ras al-Khaimah (Vereinigte Arabische Emirate)’, in: Archiv fur Orientforschung XXXIV, Vienna, pp. 237-242